Lower back pain is one of the most prevalent health challenges in modern society, with statistical estimates suggesting that approximately 80% of individuals will experience it at some point in their lives. A lower back strain—often caused by damage to muscle fibers or tendons—can feel debilitating initially, but most cases improve significantly within a few weeks through proper non-surgical interventions and corrective exercises. This analytical report provides an evidence-based perspective on injury mechanisms, methods to differentiate muscle pain from serious spinal issues, and standardized exercise protocols.

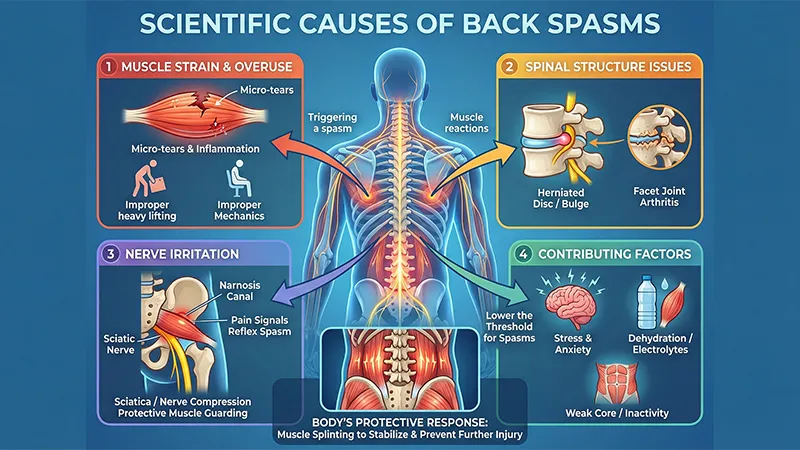

The Science of Back Pain: Why Lower Back Muscles Get Strained

The lumbar spine serves as the primary axis for transferring weight from the torso to the lower extremities. It must support static loads while resisting dynamic forces from twisting, bending, and lifting. Stability in this region is provided by the “Canister Model,” where the diaphragm at the top, the pelvic floor at the bottom, and the abdominal and back muscles at the sides create optimal intra-abdominal pressure that supports the vertebrae like an internal medical belt.

A muscle strain occurs when the forces applied to the muscle exceed its bearing capacity, leading to microscopic tears in soft tissue and triggering an inflammatory response. While the initial instinct is often absolute rest, modern research shows that prolonged inactivity can lead to weakness in stabilizing muscles and chronicity of pain. The goal of stretching is not just to lengthen the muscle, but to restore the biomechanical balance between strength and flexibility.

Muscle Strain vs. Herniated Disc: How to Identify Your Pain

Differentiating the source of pain is a vital step in management. While muscle strains typically remain localized in the lower back, more serious issues like herniated discs or spinal stenosis often present with neurological symptoms.

| Clinical Feature | Muscle Strain | Herniated Disc | Sciatica |

| Main Pain Location |

Localized to the lower back and buttocks |

Back pain radiating into the legs |

Nerve path from buttocks to below the knee |

| Type of Sensation |

Dull ache, stiffness, or muscle spasms |

Sharp, shooting, sudden pain |

Burning, tingling, or “electric shock” |

| Effect of Movement |

Worsens with direct muscle use |

Worsens with sitting, sneezing, or coughing |

Worsens with direct nerve stretching |

| Neurological Signs |

Usually absent |

Muscle weakness and reduced reflexes |

Numbness in the calf or foot |

Dangerous Red Flags: When to Seek Immediate Medical Care

Some symptoms indicate severe pressure on nerve roots (such as Cauda Equina Syndrome) or vascular issues (such as an Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm). Seek emergency care immediately if you experience:

Sudden loss of bladder or bowel control.

“Saddle anesthesia” (numbness in the groin, buttocks, or inner thighs).

Progressive leg weakness that makes walking or standing impossible.

Severe pain following a traumatic injury like a car accident or fall.

High fever accompanied by back pain (possible spinal infection).

Home Treatment Phases: From Inflammation Control to Recovery

Modern rehabilitation focuses on early, controlled movement. Using ice for the first 48–72 hours helps reduce inflammation, followed by heat to relax tight muscles. Avoid absolute bed rest, as it causes connective tissue stiffness and reduced blood flow.

Managing Pain During Exercise: The 0-5 Pain Scale

To ensure safety, use a pain scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain). NHS guidelines recommend keeping exercise within the 0 to 5 “acceptable pain” range.

| Pain Level (0-10) | Description | Recommended Action |

| 0 to 3 | Minimal pain |

Continue exercises at a normal pace |

| 4 to 5 | Acceptable pain |

Continue with caution and focus on form |

| 6 to 10 | Excessive pain |

Stop and reduce intensity or repetitions |

Physiotherapists also use the “2-hour rule”: if pain from exercise lasts more than 2 hours after finishing or leads to increased morning stiffness the next day, the intensity was too high and must be adjusted.

Diaphragmatic Breathing: The Key to Core Stability

Many patients instinctively hold their breath when in pain (the Valsalva maneuver), which increases muscle tension and disc pressure. Diaphragmatic (belly) breathing activates the parasympathetic nervous system for relaxation and regulates intra-abdominal pressure to stabilize the spine.

How to Perform Correct Breathing: Lie on your back with knees bent. Place one hand on your chest and the other on your belly. Inhale deeply through the nose so the hand on your belly rises while the chest remains still. Exhale slowly through pursed lips for twice the duration of the inhale. Practicing this for 5–10 minutes daily is foundational for controlling muscle spasms.

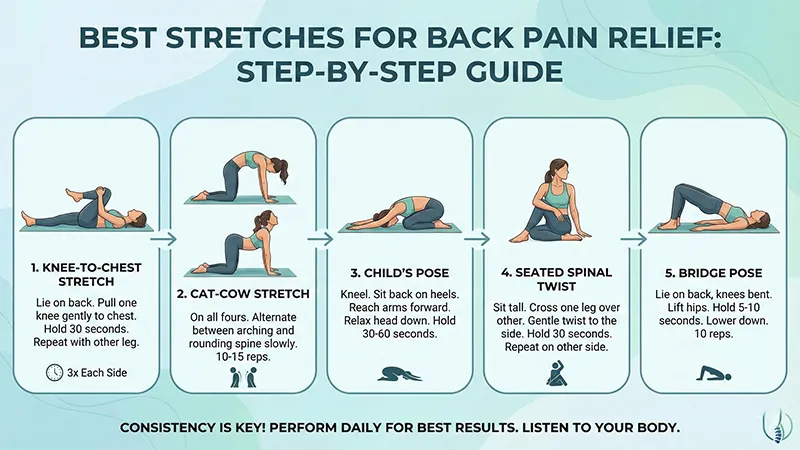

Step-by-Step Guide to the Best Lower Back Stretches

Stretches should be performed slowly and without bouncing (ballistic movements). Dynamic stretches are best for warming up, while static stretches are ideal for increasing muscle length at the end of a session.

1. Knee-to-Chest Stretch

This is the “gold standard” for opening facet joints and stretching the lower back and gluteal muscles.

Method: Lie on your back. Pull one knee toward your chest with both hands. Tighten your abdominals and press your spine to the floor.

Timing: Hold for 20–30 seconds. Repeat 2–3 times for each leg.

2. Lower Trunk Rotation

This movement increases the rotational mobility of the lumbar vertebrae and improves the flexibility of the obliques.

Method: Lie on your back with knees bent and feet flat. Keeping shoulders on the floor, slowly roll your knees to one side.

Caution: Only move within a range that causes no pain. Hold for 5–10 seconds per side.

3. Cat-Camel Stretch

This exercise coordinates the entire spine and helps redistribute forces in soft tissues.

Method: On all fours, arch your back toward the ceiling while tucking your chin (Cat), then let your belly sag toward the floor while looking forward (Camel/Cow).

Repetitions: 10–15 slow repetitions coordinated with breathing.

4. Piriformis Stretch

The piriformis muscle is deep in the buttock; its tightness can be a source of radiating pain.

Method: Lie on your back, cross your right ankle over your left knee. Grab your left thigh and pull it toward your chest.

Effect: This relieves pressure on the sciatic nerve and reduces pelvic tension.

5. Child's Pose

A relaxing yoga pose that provides longitudinal stretch to the paraspinal muscles.

Method: Kneel and sit on your heels. Fold your torso forward, resting your forehead on the floor and extending your arms ahead.

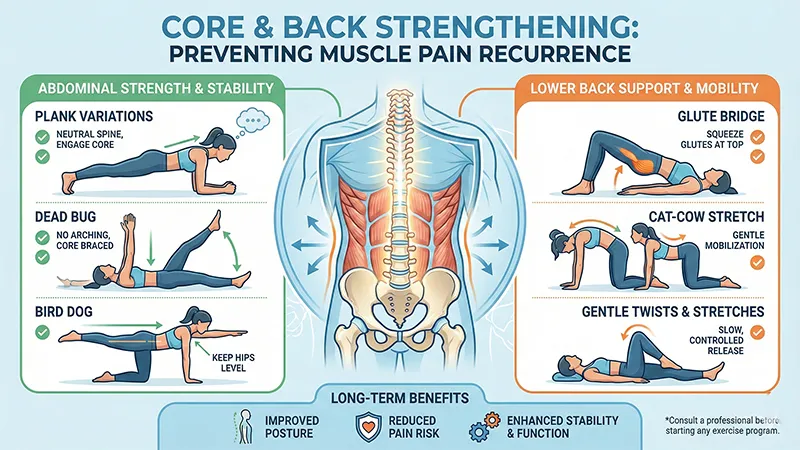

Strengthening the Core to Prevent Recurring Injury

Stretching alone is not enough; the “core” muscles must be strengthened to protect the vertebrae from shearing forces.

1. Bridging

Strengthening the glutes and hamstrings provides a strong foundation for the spine.

Method: Lie on your back with knees bent. Squeeze your buttocks and lift your hips until your body forms a straight line from knees to shoulders.

2. Pelvic Tilt

This teaches patients how to keep their lower back in a “neutral spine” position.

Method: Lie on your back. Flatten your lower back against the floor by tightening your stomach muscles without lifting your hips.

3. Bird-Dog

Ideal for strengthening posterior stabilizers and improving balance without overloading the vertebrae.

Method: On all fours, simultaneously extend the opposite arm and leg, holding for 5–10 seconds while keeping the back flat.

Common Mistakes and Forbidden Exercises in Back Rehab

Certain classic exercises are dangerous for a strained back and can worsen a muscle pull into a disc herniation.

| Exercise to Avoid | Why it is Harmful | Safe Alternative |

| Standing Toe Touches |

Excessive stress on spinal discs and ligaments |

Hamstring stretch using a towel or sitting |

| Full Sit-ups |

High torque on the lumbar vertebrae |

Partial Crunches |

| Double Leg Lifts |

Increases lower back arch and facet joint pressure |

Single leg lifts or bridging |

| Ballistic Stretching |

Causes micro-tears in muscle fibers |

Slow static stretches |

The mantra “No Pain, No Gain” is a dangerous myth in back rehab. Any stretch causing sharp or shooting pain must be stopped immediately.

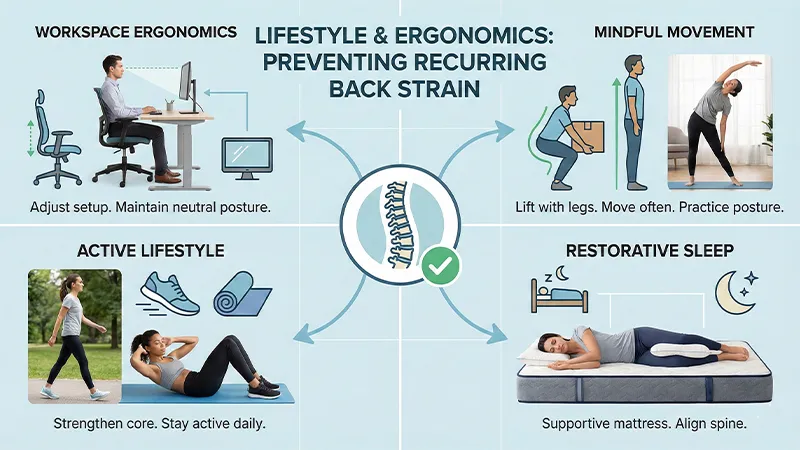

Ergonomics and Lifestyle: Preventing Re-Injury

Recovery requires correcting how you interact with your environment throughout the day.

Correct Lifting: Never bend from the waist to pick up objects. Always bend your knees, keep the object close to your body, and avoid twisting while carrying a load.

Sleep Positions: Avoid sleeping on your stomach as it flattens the natural spinal curve. Sleep on your back with a pillow under your knees, or on your side with a pillow between your knees.

Sit Less: Sitting increases disc pressure by 40% compared to standing. Stand up every 30 minutes for a quick walk or stretch.

Summary and Recovery Strategy

Managing a lower back strain is a multi-faceted process moving from inflammation control to functional activity. The keys to success are “consistency in practice” and “listening to your body.” Most back pain improves with conservative methods, but if there is no progress after 4–6 weeks, consultation with a physical medicine specialist or spine surgeon for further imaging (like an MRI) is necessary.